Carolina Fusilier – My first loves were music and photography. Since I was 12, I dreamt of playing in a band and writing my own songs. I was part of some music projects over the years but nothing long-lasting. When I was 15, I signed up for a photography class at a local bookstore. There was an old family Canon camera that I learned to use and I would take it with me everywhere, building surreal scenes with my friends using lights and mirrors. It was almost 2000 but my family didn’t own a computer yet, so discoveries were made more through chance and word of mouth. Growing up during this pre-internet moment was so special and dear to me because you paid attention to coincidences, navigating forms of encounters that were often magical.

When I got older, I enrolled at a small film school near San Telmo in Buenos Aires. I knew early on that I didn’t identify with the way they taught us to make films: how there’s always a character, a script, a storyline, and so on. It didn’t feel like my medium, or at least not my format for storytelling. I left after a year and decided to live with my relatives in Canada for some months, where I worked as a waitress and joined a workshop at a very eccentric place called QuickDraw Animation Society. Discovering artists such as Norman McLaren, Caroline Leaf, Oskar Fischinger, and Stan Brakhage was eye-opening and changed the way I understood film. I instantly connected to how animation explores the interception of sound and moving images, it incorporated everything I loved.

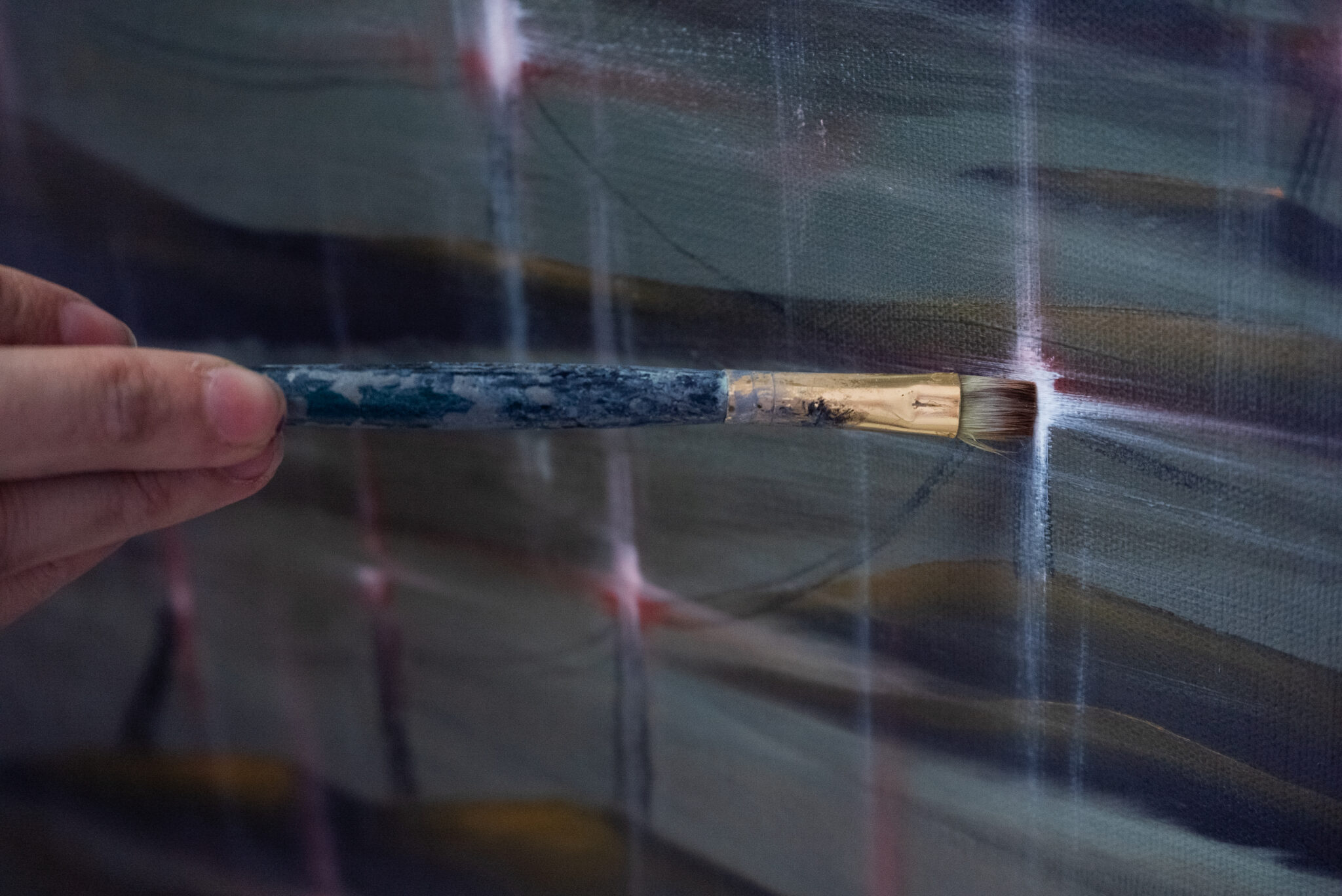

Later, I came back to Buenos Aires, started painting classes, and enrolled in another animation program. It was 2010, I was living in a shared house in La Boca, a neighborhood in Buenos Aires, and was selected to do an art program for a year. That encouraged me to dive deeper into my art practice and made me realize that I had arrived where I belonged, that the freedom in artmaking encompassed the many interests and ideas I had been sowing all those years.

The world of schools and institutions often requires one to be specific about their aspirations, but in my own way, I managed to explore everything that excited me. However, I occasionally felt that external pressure to define myself as something: a painter, a musician, a filmmaker. I did not want anything to contain me and still wanted to hold it all.

The dance between fact and fiction is pronounced in your work. In your film Mercurial Currents (2023), you reexamine a personal trauma, which feels related to this tension of fact and fiction commingling in the recounting of an event. Could you talk a bit about that?

Imagine a glowing, golden bubble full of foreign capital suddenly emerging, silently floating, hypnotizing all who cross its path. That’s how the 90s felt in the socioeconomic context I grew up in. My family fell under a kind of spell that ultimately resulted in a national financial crisis. The radical changes in the value of the Argentine peso permeated every home and economic class, breeding a lot of confusion and, ultimately, a new desire for social progress, new commodities, and global capitalization. Mercurial Currents was the first time I confronted a personal history—including that of my family and my generation in Argentina—through my art practice in such a direct way. Growing up during this time left impressions on me that I am continuously processing and unpacking.

The film revolves around a photo of my father that appeared in the newspaper during the 1990s when he worked for a stockbroker in the trading room of the Buenos Aires Stock Market. I played between factual and fictitious stories that stemmed from my search for this photograph, as my father still denies it’s him. There is something freeing about not naming places, people, or dates when discussing archival material. A historically specific event, like the 2001 financial crisis in Argentina, suddenly becomes atemporal, and it’s this disorientation of time that reveals the cyclical nature of human crises and collapses.

With this more recent work, I opened up my need to expose personal and familiar stories and resurface the economic difficulties we faced during a complex moment in Argentinian history. Part of the process of making this project also helped to shed light on the mystery of the artist economy—how one sustains their practice, their way of life—and this felt necessary to articulate, breaking an uncomfortable silence sustained during those many years of living and making work in this Latin American context.

Rather than try to explain the technology and ambiguous forces that control contemporary society, you often imbue them with fantasy and personality instead. What do you have in mind when rendering these sci-fi-esque scenes?

In terms of depicting technology, I always try to project a sense of animism. All of the elements I render have souls, including ambiguous and complex things like finance, a city sewage system, a stove, or a washing machine. From an animist perspective, technology doesn’t die but regenerates new life independent from humans. In my fascination with the animated, I find myself right back at my first encounters with moving images and animation, and it’s funny to see how that influence shows up again in unpredictable and humorous ways. For instance, in the Mercurial Currents exhibition at Museo Jumex in 2023, there is an installation work called Choir of Telephone Zombies (2023) that consists of 10 old office phones synchronized with the film and programmed to be activated in a choreography of light and sound. Another example is Last Sunsets (2018), where I wrote and recorded a dialogue between a refrigerator, a washing machine, and an oven that discuss about their afterlife in this sort of limbo of broken domestic machines.

I’m very inspired by the blurred boundaries between science and speculation. Art allows us to imagine possible worlds, or the world as we know it, but under new laws, be they scientific, political, economic, or social. I enjoy thinking that every thing has a voice and feelings and can also testify to history from a non-human angle. My belief in mechanical consciousness and the organic aspect of machines likens my work to sci-fi traditions. I always look for this displacement of perspectives because you can see yourself from the outside and laugh about how ridiculous and minuscule we are as a species.

Between the temporal and animistic components of your work, there’s an overarching theme of shedding light on the invisible. I’m curious about the new body of work that was on view in Isla Eléctrica at Peana this summer, and how it may or may not respond to this notion of the unseen.

A big part of the filmmaking process involves the exploration of sound, and in terms of what you’re asking, sound brings to life the unseen world. Some of the process of designing sound and foley is searching for strange, distinct, and unaltered noises produced by objects you’d never expect. During the making of El Lado Quieto (The Still Side) (2021), a feature film I made in collaboration with my partner Miko Revereza, we explored the architectural ruins on the coast of Guerrero, Mexico, through its soundscape. We stuck electromagnetic microphones, water mics, and tiny wire-tap mics onto the decaying pipes of surrounding buildings. We created the film’s entire sound from these recordings, ascribing a “voice” to each of the locations and structures we filmed. The role of the audible in working with film is a key element to approach differently what we see. Building sense in this relation of seeing and hearing is something fascinating when I’m editing.

Isla Eléctrica (2024) began when I first heard the sound of dried clay dissolving in water through a hydrophone. It sounds like a ticking clock, a gastrointestinal gurgle, or a clanking machine. But, what I love the most is the act of espionage through sound, accessing events that are invisible to the eye. In this case, we are hearing the displacement of air as water penetrates the clay’s pores, an encounter between elements that generates a material transformation. It’s mind blowing to be able to hear such a specific sound!

The Metabolic City (2024) is a series of sculptures created in collaboration with a local artist and neighbor called Waz. We made them to be submerged and decomposed in water. This sound was always the thread running through this group of works, so I decided to write a kind of manifesto about it. Manifesto of a Metabolic Community (2024) is an introductory video to the narratives of Isla Eléctrica and functions as an image-portal projected over the entryway of the main gallery.

The voiceover accompanying the underwater scenes belongs to an inhabitant of the ‘Metabolic Community:’ creatures transitioning from terrestrials to deep-river dwellers. “Stability, durability, are terrestrial logics that we are leaving behind,” says this character in an abstract language (the underwater bubbling sounds of clay dissolving). One of the inspirations for this manifesto was the post-war Metabolic Architecture movement in Japan whose utopian vision aimed to break with traditional architecture and called for organic, mutant structures that naturally change. In contrast, Mexican modernism in the 1950s transformed the country’s landscapes with metal and concrete. The voice of the Metabolic Community is soft and permeable against the tyrannical models that impose durability. Their basis as a civilization is the search for a material transformability that merges with the currents of the river.

This idea of generation through transition moves me at a deeply personal level. The exhibition includes sound activations that amplify the sound of the clay structures submerging in real-time. It became a kind of therapy for me, producing a series of structures to throw into the water. Drowning these buildings made of clay became a stand-in for releasing old beliefs and limiting notions of success and materialistic stability, ideals one unconsciously adheres to because of the world we live in. Each submerged structure that collapses and mutates gradually deconstructs these ideals and desires, unlearns what has been learned, transitions, and surrenders to constant change.

Interview conducted and translated for Art21 in August of 2024 by Carina Martinez. Original photography for Art21 by Miko Revereza in June 2024. All additional photography courtesy the artist and PEANA. Click here to read the Spanish version.

Ian Forster – Could you tell me how this project began and how this particular installation is a part of that?

Michael Rakowitz –The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist began in 2006, but it’s a project, I think, that began before that in 2003. In the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq, the National Museum of Iraq was looted in Baghdad from the 10th until the 12th of April of that year. In that museum, you have some of the earliest examples of writing, of urban planning. It’s a primal scene of human history.

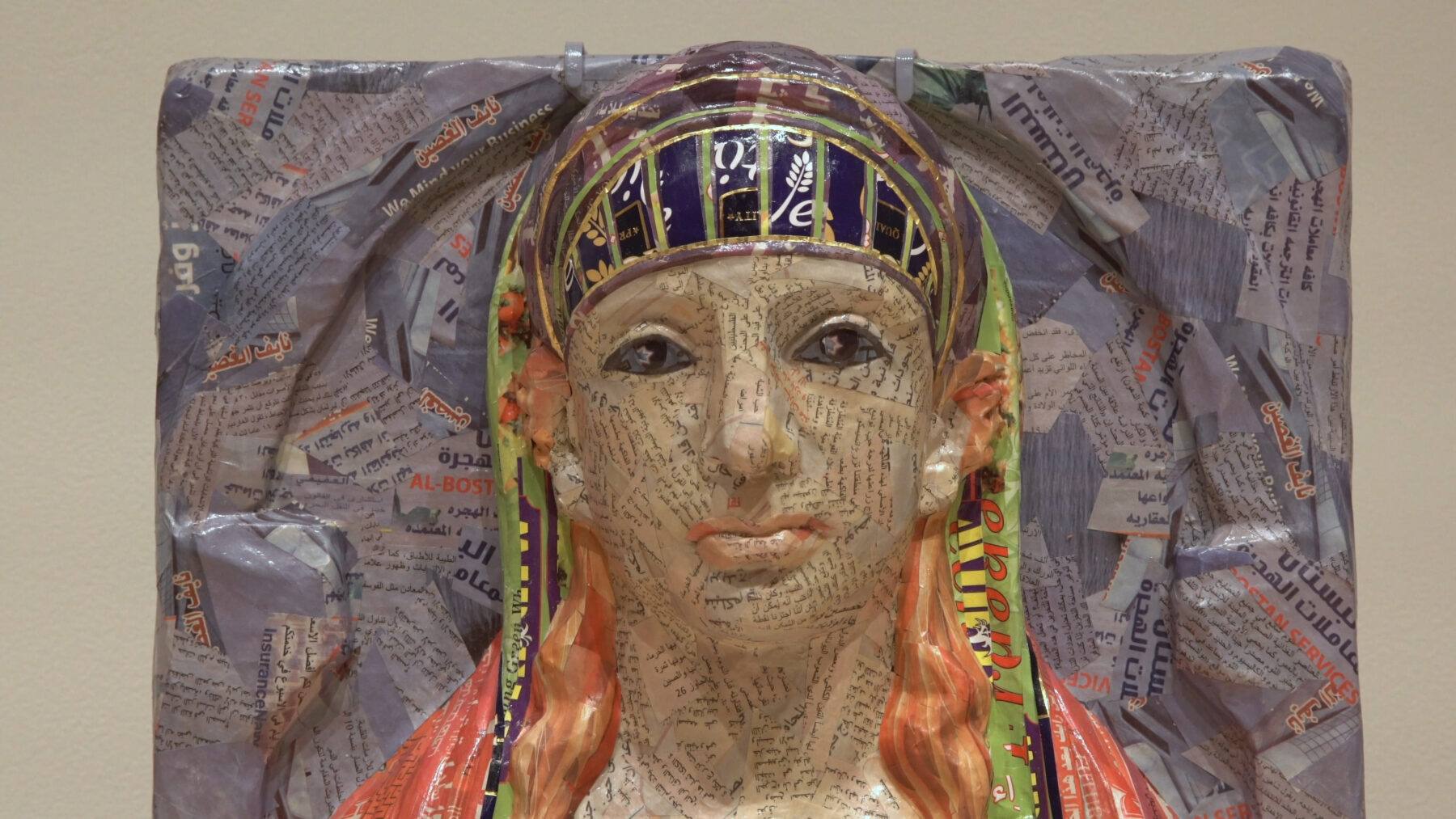

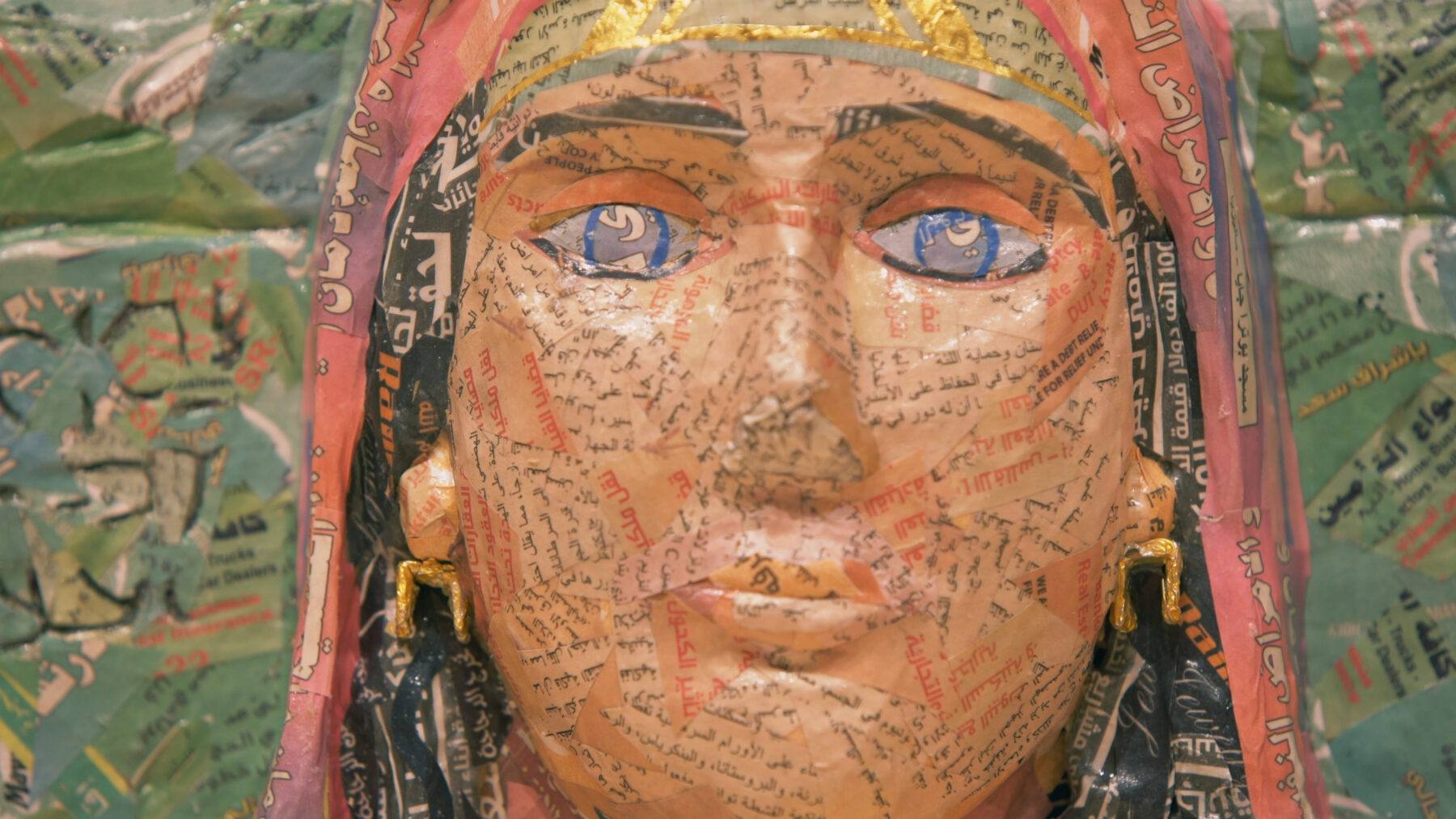

And when the outrage about lost artifacts did not turn into an outrage about lost lives, I started to think about a project with those artifacts that were listed as missing, stolen, destroyed, or status unknown on the various databases that look to inventory what had been lost from the Iraq Museum. I decided that it would be interesting to, not reconstruct, but reappear those artifacts as a spectral presence. As a ghost of what once was. And so it began as a project where I focused entirely on the 8,000-plus artifacts that are still at large in the aftermath of the looting of the Iraq Museum, but it’s also unfortunately grown to include the archeological sites that have been devastated by groups like ISIS in the wake of the Iraq War.

When that initial looting occurred, what was the international reaction?

The reaction at the moment of the looting was one where the ability for humans to focus on the direct tragedy may have been redirected through these objects. This is something that often happens through trauma—we focus on something that becomes a vessel for other forms of grief and rage. But it also is a telling moment in that it aligns with other historical moments of iconoclasm or vandalism or libricide, and the burning of books, as we know, is accompanied by the burning of people. So when we see the cultural heritage of a place being destroyed or being looted in the aftermath of a violent invasion, we start to see the ways in which that culture reflects on what’s happening. I think that the project as a whole, even with the works that are destroyed by ISIS, points to the fact that the West assigns value to the objects from that part of the world. But it’s not at all symmetrical when you consider the way in which there’s been this devaluation and dehumanization of the people that are from those places.

You mentioned a few times now that ultimately what you’re most interested in is the people, and, of course, it’s very personal for you. Can you talk about this work’s connection to your family background?

Okay. So, my mother’s family was from Baghdad. They were Jews that lived in that city and were put in a position where they had to leave in the mid-1940s. And they were proud to identify as Arab Jews. The house that they had in New York when they left the Middle East was set up so that they could transmit this culture that they were heartbroken to be torn away from. And those aromas, that evidence of human gathering and conversation and warmth in the family, was something that filled this architectural space in a way where I was mesmerized. That really laid the groundwork of having some understanding of who we were and where we were from, but it wasn’t exoticized. It wasn’t something that felt in any way alien to me, and I think that’s evidence of the fact that my grandparents were able to do what I think a lot of immigrant families try to do, which is how do you preserve where you’re from when you’re forced to move to somewhere else?

This was something that I saw reflected so much in the commodities that one finds throughout grocery stores in the United States and in cities like New York, which I grew up in close proximity to, specifically Sahadi Importing Company in Brooklyn. There was one moment in particular that frames my entire practice, when I was in the store in 2004, and saw a big red can of date syrup that had Arabic writing on it that said ‘product of Lebanon.’ And I thought to buy this for my mother, because date syrup is actually something that’s very important to Iraqi cuisine and we grew up around it.

I walked up to the cash register, and the owner of the store, who knew my grandparents when they first immigrated from Iraq, said to me, “Your mother’s going to love this. It’s from Baghdad.” I looked at the can and it said ‘product of Lebanon.’ And I wondered what was going on, what was this strange geography lesson? He said to me that the date syrup is actually processed in the Iraqi capital, put into large plastic vats, then driven over the border to Syria, where it gets put into these unmarked tin plate steel cans, and then it’s driven over into Lebanon, where it gets labeled and is sold to the rest of the world. And this was one of the ways in which the Iraqi date syrup industry survived during the years of the sanctions, from 1991 until 2003.

But this was 2004, a year after the sanctions had been dropped, and I wondered why it was still in place. The owner said to me, “Because of the prohibitive charges from US Homeland Security, for anything that is coming from a place like Iraq or Afghanistan, it would be too prohibitive for somebody to import it. And therefore, it would be bad business.” And I said, “Well, it could be good art.” And so that birthed Return (2004-Ongoing), a project where I reopened my grandfather’s import-export company that he operated in Baghdad, and I operated it here in Brooklyn with the chief directive to import Iraqi dates to the US for the first time in 40 years.

Through the import-export industry, I started to learn about all these commodities that were too scared to tell you where they were from. It was almost like the pressures of xenophobia were being exerted on the object itself. And it was in that moment, when I was operating what was basically an empty store in Brooklyn, that I started to think about the emptied out museum in Baghdad. And when I started to think about the object in the vitrine in the museum, which holds its value because of where it comes from, I thought about the date syrup and date cookies not being able to tell you where they were from. I thought that was the skin that these artifacts should have to wear when they come back as ghosts. That’s how they should appear: in this urgent, vulnerable materiality that is about people having to leave that place and then what they do to survive. Not just to keep breathing, but to keep living a life where they feel like they’re still belonging to a place while also pointing to the fact that they are no longer there, and not by conditions of their own making.

What other materials are the objects in the installation made of?

These reliefs themselves continue the material culture of the larger project, which is to use the packaging of Middle Eastern food stuffs and Arabic English newspapers that are found throughout the United States in different groceries, which are often gathering spaces for a lot of families who come from places like Palestine, Syria, Iraq. In those places, where they get the spices and different ingredients to continue to make their cuisine, they also get these Arabic English newspapers that are given away for free. And so that newspaper shows up in these reappearances as well. One of the things that’s interesting about the particular focus on the Northwest Palace of Nimrud is that it was built by an Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal the Second in the middle of the 800s BC. And the places in Chicago where I gather the materials from are operated mostly by immigrants from Northern Iraq, so they are the direct descendants of the people that made the original reliefs. And so there’s this nice circular economy, that the hands that made these in the first place are being resurrected in some ways, are being reanimated by the professions that their descendants have taken on in this new part of the world.

Interview conducted for Art21 in January of 2020 by Ian Forster and edited in March 2023 by Carina Martinez. To learn more, watch “Michael Rakowitz: Haunting the West.”